While we’ve recently written about different types of mappings, there’s also a wide variety of subjects to make a map about. Today, we’re taking a look at issue, argument and information mapping: what are the differences, and what approach should you choose when unsure?

Issue mapping

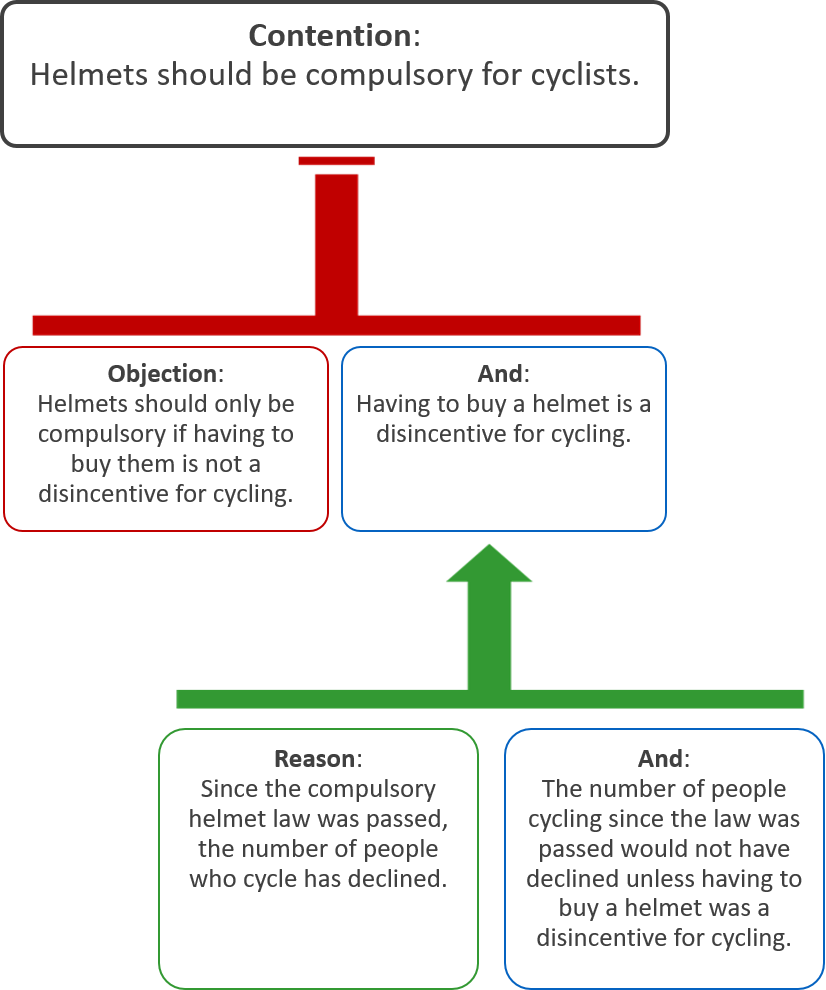

Issue mapping revolves around, you guessed it, issues. These issues are treated as to-be-answered questions. To resolve the issues, possible answers are posed (‘positions’) which are supported by arguments. In issue mapping, both supporting and counter arguments are used – commonly called ‘pros’ and ‘cons’. The goal of an issue map is to map out the structure of a conversation as seen by all its participants. In that sense, they are very different from, for instance, flowcharts. However, there are also some similarities: just like other mapping techniques, issue mapping puts elements in bubbles which are connected by arrows.

Issue mapping is based on IBIS, or the issue-based information system, a concept invented by German design theorists Werner Kunz and Horst Rittel in the 60’s. IBIS is a graphing method to clarify complex issues by focusing on argumentation.

Kunz and Rittel used a specific term for these complex issues: ‘wicked problems’. Wicked problems are ill-defined and usually involve multiple stakeholders. In this case, wicked doesn’t mean evil: rather, it refers to the difficulties of resolving such issues. They are challenging because of incomplete, contradicting and changing elements. In 1973, Rittel and his colleague Melvin Webber came up with ten characteristics of wicked problems, focused on social policy issues:

- Wicked problems do not have a definitive formulation

- Wicked problems don’t have a stopping rule, which is to say that it is not possible to calculate stochastically when the process will be over

- There’s no right or wrong solution to a wicked problem, only better and worse outcomes

- There is no way to immediately test a solution to a wicked problem

- There is no possibility for trial and error with wicked problem solutions

- Solutions to wicked problems are not countable

- Wicked problems are unique

- Wicked problems are symptoms of other problems

- There are many explanations to wicked problems, all of which lead to different resolutions

- People who execute the solutions are liable for the consequences of their actions

This seems like quite the complex list, and its related wicked problems are too. Some examples of wicked problems are the AIDS epidemic, climate change, international drug trafficking and homelessness. Of course, however, we are allowed to step away from this and take on complex issues regardless of whether they fit each check-point. The issues we choose to map in an issue map do not have to be of the uttermost complexity that climate change is.

Some important steps that you might follow to create an issue map, are as follows:

- Aim to identify the issue you want to examine

- Analyze what the related issues are

- Create a hierarchy of the relationships of these issues in a map

- Determine pros and cons of these issues, and add these to the issues

Resort to issue mapping when:

- You believe you’re dealing with a ‘wicked issue’

- You want to make your process more transparent

- You want to analyse (potential) issues through pros and cons

Argument mapping

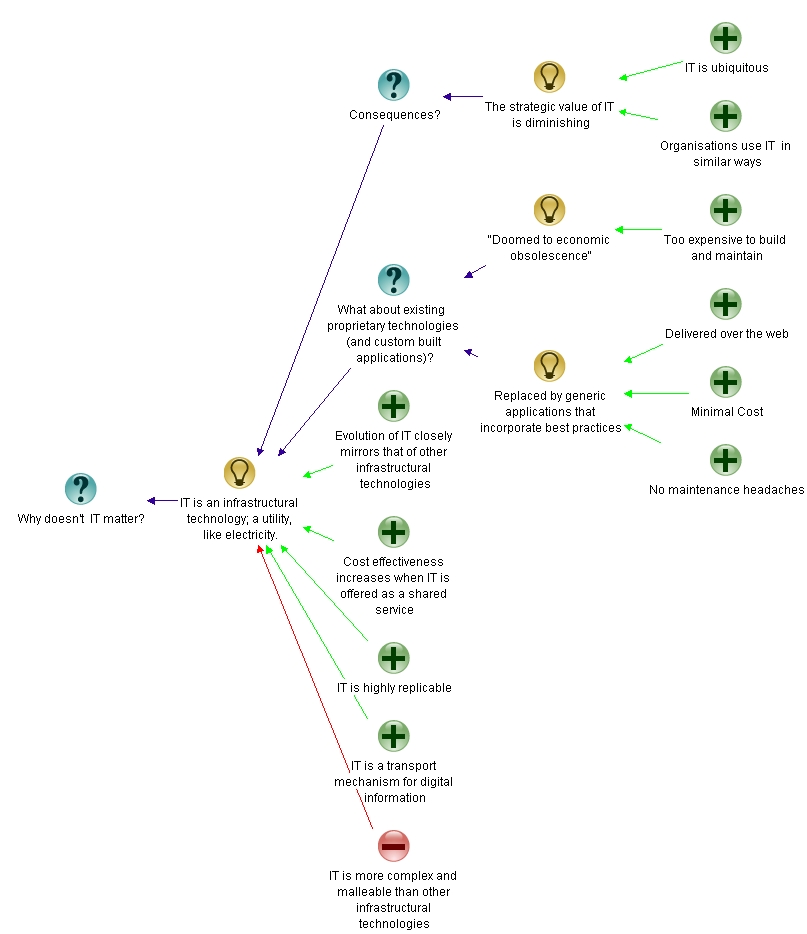

Argument maps focus on representing the structure of arguments. While similar to issue mapping, argument mapping is different in the sense that they focus on discussions between people more strongly than issue maps. The most standard version of an argument map is the standard diagram, a tree-shaped map which includes several arguments leading to the concluding argument. This conclusion can be either at the top or at the bottom.

Argument maps aim to include all the key elements of a specific argument. This is done through focusing on several traditional logical elements of arguments: through certain justifications, which are assumptions of truth (‘reasons’ or ‘premises’) we achieve the conclusion (‘main contention’). This way of reasoning can be accompanied by, for instance, counter arguments, co-premises and objections. While arguments are traditionally numbered and connected by arrows, software has made it easier to include the full arguments in the mapping without numbers.

There are several ways to display elements in argument maps. With the mapping above, for instance, we can see that both the reason and objections are not independent, but are adjoined by an ‘and’ statement. This becomes clear by the connecting line. At the same time, we are aware of the difference between pro and con through the red and green colour difference.

To create an argument map, keep this in mind:

- Identify the topic you want to argue on and establish your main point of view

- Start considering what drives this point of view and write it down in logical order

- Analyze what the counter arguments of such a viewpoint might be, and add them in the mapping

You will see that argument maps are excellent at uncovering the logical structure behind an argument. It will also help you evaluate your argument and see where work needs to be done to improve it.

Resort to argument mapping when:

- You want to chart out the elements of an argument step-by-step for better understanding

- You want to evaluate potential arguments in a discussion – spin doctors use this technique all the time 😉

- You hope to improve your reasoning and critical thinking skills

Information mapping

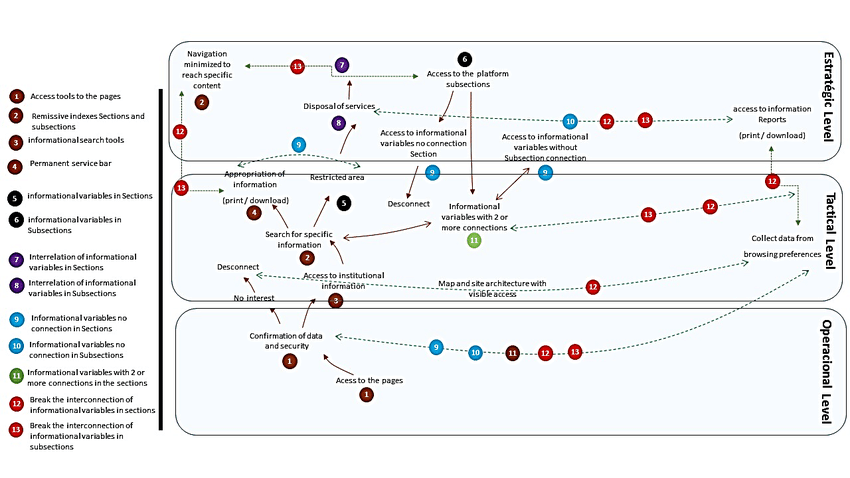

With information mapping, we aim to establish a clear overview of a set of information. It is a technique developed by political scientist Robert E. Horn in 1967, who intended to represent information easily in a visual structure. Information maps are used to clearly and systematically approach a set of information, making it easy to understand at a later point in time.

Information maps follow Horn’s approach to categorize information based on their purpose for the reader:

- Procedure information focuses on what steps need to be taken to complete a task

- Process information focuses on events that take place within a certain timeframe which have a specific result

- Principle information focuses on guiding behaviors

- Concept information focuses on a certain set of information that falls into the same category

- Structure information focuses on describing something which has certain limitations or boundaries

- Fact information focuses on true statements

The overall process of information mapping consists of three stepping stones. These are analysis of the information, organizing what you’ve found, and clearly presenting it in a map. Additionally, there are six principles that the information mapping method follows in order to clearly structure it:

- Chunking principle

- Relevance principle, which demands that each unit is limited to a single topic

- Labeling principle, which demands the contents are to be labeled to identify units

- Consistency principle, which demands that we are consistent in organizing the information and using certain terms

- Accessible detail principle, which demands that we make the details of information easily accessible but also easily skippable

- Integrated graphics principle, which demands we use visuals to emphasize and clarify information

We can create information mappings when we:

- Aim to display information in a clear way

- Make information easy to access at a later point in time

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issue-based_information_system

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/BF01405730.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argument_map

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_mappinghttps://medium.com/technical-writing-is-easy/information-mapping-in-technical-writing-5e772f7dc47c

Photo by Patrick Perkins on Unsplash